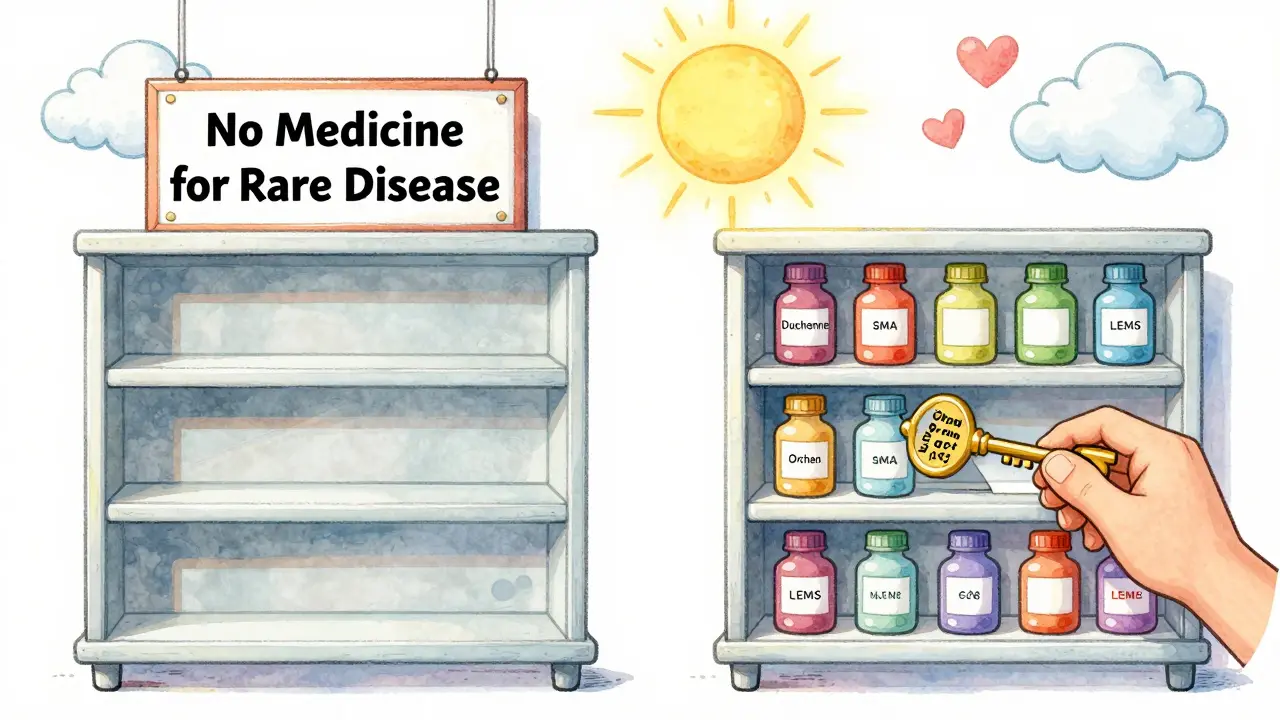

Before 1983, fewer than 40 treatments existed for rare diseases in the U.S. Today, more than 1,000 are approved. What changed? The orphan drug exclusivity system - a rule that gives companies seven years of exclusive rights to sell a medicine for a rare condition, even if patents have expired. This isn’t just a legal detail. It’s the reason life-saving drugs for conditions like Duchenne muscular dystrophy, spinal muscular atrophy, and certain rare cancers even exist.

What Exactly Is Orphan Drug Exclusivity?

Orphan drug exclusivity is a special market protection granted by the FDA to drugs approved to treat rare diseases. A disease is considered rare if it affects fewer than 200,000 people in the U.S. - or if the company can’t make back its development costs even if it sells the drug to everyone who needs it. The exclusivity kicks in the day the FDA approves the drug for that specific rare condition. During those seven years, no other company can get approval for the same drug to treat the same disease - unless they prove their version is clinically superior.This isn’t a patent. Patents protect the chemical formula or how the drug is made. Orphan exclusivity protects the use. So if a drug is approved for a rare form of epilepsy, no one else can sell that exact drug for that epilepsy type for seven years. But they could still sell it for migraines, if that’s not protected.

Why Was This System Created?

In the early 1980s, pharmaceutical companies weren’t developing drugs for rare diseases. Why? The math didn’t add up. If only 5,000 people in the country have a condition, and each dose costs $500, the total market is $2.5 million. Development costs? Often over $100 million. No company would risk that without a guarantee.The Orphan Drug Act of 1983 fixed that. Signed by President Ronald Reagan on January 4, 1983, it gave companies a powerful incentive: seven years of market exclusivity, regardless of patents. It also offered tax credits for clinical trial costs and waived FDA application fees - worth about $3.1 million per drug today. The result? Before 1983, only 38 rare disease drugs had been developed in the U.S. Since then, over 1,000 have been approved.

How It Works: The Horse Race for Approval

Here’s the twist: multiple companies can apply for orphan designation for the same drug and disease. But only the first one to get FDA approval wins the seven-year exclusivity. It’s like a race. Ten teams might be running for the same finish line - but only the first to cross gets the prize.That’s why timing matters. Companies often file for orphan designation during early clinical trials - Phase 1 or 2 - to lock in their position. The FDA reviews these applications in about 90 days and approves 95% of them if the disease prevalence is clearly under 200,000 people.

And here’s another key point: exclusivity doesn’t stop generics from selling the same drug for other, non-orphan uses. Take amifampridine. It was approved for Lambert-Eaton myasthenic syndrome (LEMS), an orphan condition. But it’s also used for other muscle disorders. Once the orphan exclusivity expires, generics can enter the market for those other uses - even if the LEMS use remains protected.

How It Compares to Other Countries

The U.S. gives seven years. The European Union gives ten. And in Europe, companies can get an extra two years if they test the drug in children. The EU also has a way to reduce exclusivity from ten to six years if the drug turns out to be more profitable than expected - something the U.S. doesn’t do.That’s why some companies target the U.S. market first. Seven years is still long enough to recoup costs, and the process is faster. The FDA has approved over 1,000 orphan drugs since 1983. The EMA has approved fewer than 200. The U.S. system is more aggressive - and more successful.

What Counts as ‘Clinically Superior’?

If another company wants to launch a competing drug for the same rare disease during the exclusivity period, they must prove their version is clinically superior. That means better safety, better effectiveness, or a major improvement in how the drug is delivered - like switching from an IV to a pill.But here’s the reality: it’s almost impossible to meet that standard. Since 1983, there have been only three documented cases where a second company successfully proved clinical superiority. In most cases, the first company holds the market alone for the full seven years.

Who Benefits - and Who Doesn’t?

Patient groups overwhelmingly support the system. A 2022 survey by the National Organization for Rare Disorders found that 78% of advocacy groups consider orphan exclusivity essential. Without it, they say, no one would develop treatments for their conditions.But critics point to abuses. Some companies have filed for orphan status on drugs that already had large, profitable markets. Humira, for example, received multiple orphan designations even though it treats common autoimmune diseases. That allowed the maker to extend exclusivity beyond its patent life - and keep prices high.

Generic manufacturers argue this distorts the system. They say orphan exclusivity was meant for drugs that wouldn’t otherwise be developed - not for blockbuster drugs that just got a new label.

Market Impact: A Billion-Dollar Engine

Orphan drugs are no longer niche. In 2022, they made up $217 billion in global sales - 24.3% of the entire prescription drug market. Oncology leads the pack, with nearly half of all orphan approvals going to cancer drugs. Neurology, blood disorders, and metabolic diseases follow.By 2026, experts predict orphan drugs will account for over 21% of global prescription sales. And by 2027, more than 70% of all new drugs approved by the FDA will have orphan designation. That’s up from just 51% in 2018.

What’s Next? Pressure for Reform

The system is working - but it’s under scrutiny. The FDA recently issued draft guidance to clarify what counts as the “same drug,” especially after controversial approvals like Ruzurgi. Some lawmakers are pushing to add a new requirement: companies must prove there’s an unmet medical need, not just a small patient population.In Europe, regulators are considering reducing the exclusivity period from ten to eight years for drugs that sell better than expected. The U.S. hasn’t moved yet - but the debate is growing.

Still, the industry isn’t backing down. A 2022 McKinsey survey found that 94% of biopharma companies consider orphan exclusivity critical to their rare disease strategies. Without it, most say, they wouldn’t even try.

What This Means for Patients

For patients with rare diseases, orphan exclusivity means hope. It means a drug exists. It means a treatment is available - even if it costs $500,000 a year. The system isn’t perfect. Prices are high. Access is uneven. But without this protection, many of these drugs wouldn’t be developed at all.And for companies? It means they can take risks. They can invest $150 million into a drug for 8,000 people - because they know they’ll have seven years to sell it without competition. That’s the trade-off. Innovation for exclusivity. Hope for profit.

The system works because it’s simple: if you’re the first to bring a drug to market for a rare disease, you get the market. No one else can touch it. That’s the deal. And for now, it’s still the engine driving progress in one of medicine’s hardest frontiers.

How long does orphan drug exclusivity last in the U.S.?

In the United States, orphan drug exclusivity lasts seven years from the date the FDA approves the drug for the rare disease indication. This protection begins at approval and runs independently of any patents. During this time, the FDA cannot approve another company’s application for the same drug to treat the same condition, unless the competitor proves clinical superiority.

Can a drug have both a patent and orphan exclusivity?

Yes, most orphan drugs have both. Patents protect the chemical structure or manufacturing method, while orphan exclusivity protects the specific use for a rare disease. The two protections can run at the same time. In fact, orphan exclusivity often outlasts patents - but only in about 12% of cases. For the majority of orphan drugs, patent protection remains the primary barrier to competition.

What happens if two companies develop the same drug for the same rare disease?

Multiple companies can apply for orphan designation for the same drug and disease. But only the first one to receive FDA marketing approval gets the seven-year exclusivity. Others can still submit applications, but they won’t be approved during the exclusivity period unless they prove their version is clinically superior - a very high bar that’s been met only three times since 1983.

Can generics enter the market during orphan exclusivity?

Generics cannot sell the drug for the orphan indication during the seven-year exclusivity period. But they can sell it for other, non-orphan uses. For example, if a drug is approved for a rare neurological disorder and also for a common migraine, generics can launch for migraine treatment after patent expiry - even if the orphan use is still protected.

Why are orphan drugs so expensive?

Orphan drugs are expensive because they’re developed for small patient populations, making it hard to recoup high R&D costs. The seven-year exclusivity allows companies to set high prices without competition. While this incentivizes development, it also leads to pricing controversies. Some drugs cost over $500,000 per year - a trade-off between access and innovation.

Is orphan exclusivity being changed or phased out?

No - not anytime soon. While there’s debate about potential reforms - like requiring proof of unmet medical need or adjusting exclusivity based on sales - the system remains foundational. Over 90% of biopharma companies say it’s critical to their rare disease programs. The FDA continues to approve over 400 orphan designations per year, and the market is growing. The incentives work, even if they’re imperfect.

Okay but can we just take a second to appreciate how wild it is that we went from 38 rare disease drugs to over 1,000? 🤯 I have a cousin with SMA and she’s walking now because of this system. I know prices are insane, but if this didn’t exist, she wouldn’t even have a shot. I’m not saying we shouldn’t fix the abuses, but don’t throw the baby out with the bathwater. These families are fighting for every single day. 💕

It’s funny how people act like this is some kind of corporate conspiracy. The truth? Pharma companies won’t invest billions into a drug for 5,000 people unless they know they’ll have a shot at recouping it. The orphan drug act didn’t create greed-it created a pathway for hope. And yes, some companies game the system (looking at you, Humira), but that’s a loophole, not a flaw in the design. Fix the loopholes. Don’t kill the engine.

So let me get this straight: we reward companies for being the first to the finish line with a 7-year monopoly… and then act shocked when they charge $500k/year? 😂 I mean, I get the math. I do. But calling it ‘hope’ while families sell their homes to afford insulin? That’s not optimism. That’s gaslighting with a lab coat. Also, why do we let the FDA approve 95% of orphan designations without even checking if the drug’s actually novel? It’s like giving out gold stars for showing up.

Patents protect structure. Exclusivity protects indication. The distinction is elementary.

Do we not see the cosmic irony? We create systems to save the few, yet the few become the slaves of the system. The drug is a sacrament, the price a sin, and the patient… a silent offering on the altar of capitalism. Is this healing? Or is this just the latest form of sacred sacrifice?

It’s a textbook case of regulatory capture. The orphan drug designation framework exhibits severe path dependency, with rent-seeking behavior dominating the innovation landscape. The FDA’s permissive designation criteria-95% approval rate-indicate a failure of evidentiary gatekeeping. Moreover, the clinical superiority threshold is functionally non-operational due to the absence of standardized comparative effectiveness metrics. This is not innovation-it’s institutionalized monopolization.

yeah but like… i get why people are mad about the prices. i mean, my friend’s kid needs this drug and it’s like $600k a year. but if they didn’t have the exclusivity? no drug. period. so it’s a messed up trade-off. also, i think the ‘clinically superior’ bar should be lower? like, if a pill version exists instead of IV, shouldn’t that count? anyway. just saying. the system’s broken but we need it. 🤷♂️

Wait-hold on-let’s just pause for a second-because I think we’re all missing the point here-yes, the system incentivizes development, but-what about the fact that companies are now filing for orphan status on drugs that have been on the market for decades for common conditions, just to tack on extra exclusivity?-and the FDA approves it-because the criteria is based on patient count-not on whether the drug is actually new or innovative?-and then they raise the price 1000%-and call it ‘fair return on investment’?-and we sit here debating whether it’s ‘hope’ or ‘exploitation’-when the real problem is that the definition of ‘same drug’ is so vague that a company can slap a new label on a 20-year-old compound and call it a breakthrough?-and then we wonder why healthcare costs are exploding?-this isn’t a system-it’s a loophole factory-and if we don’t fix the definition of ‘same drug’ and add a real unmet need requirement-then we’re not saving lives-we’re just making billionaires.