When a child gets sick, getting the right dose of medicine isn’t just important-it’s life-or-death. Too little, and the infection won’t clear. Too much, and you risk organ damage, seizures, or worse. That’s why weight-based dosing isn’t just a best practice-it’s the standard for safe pediatric care. Unlike adults, kids don’t just need smaller pills. Their bodies process drugs differently. Their kidneys, livers, and body water percentages change as they grow. A one-size-fits-all approach? It doesn’t work. And relying on age alone? That’s how errors happen.

Why Weight Matters More Than Age

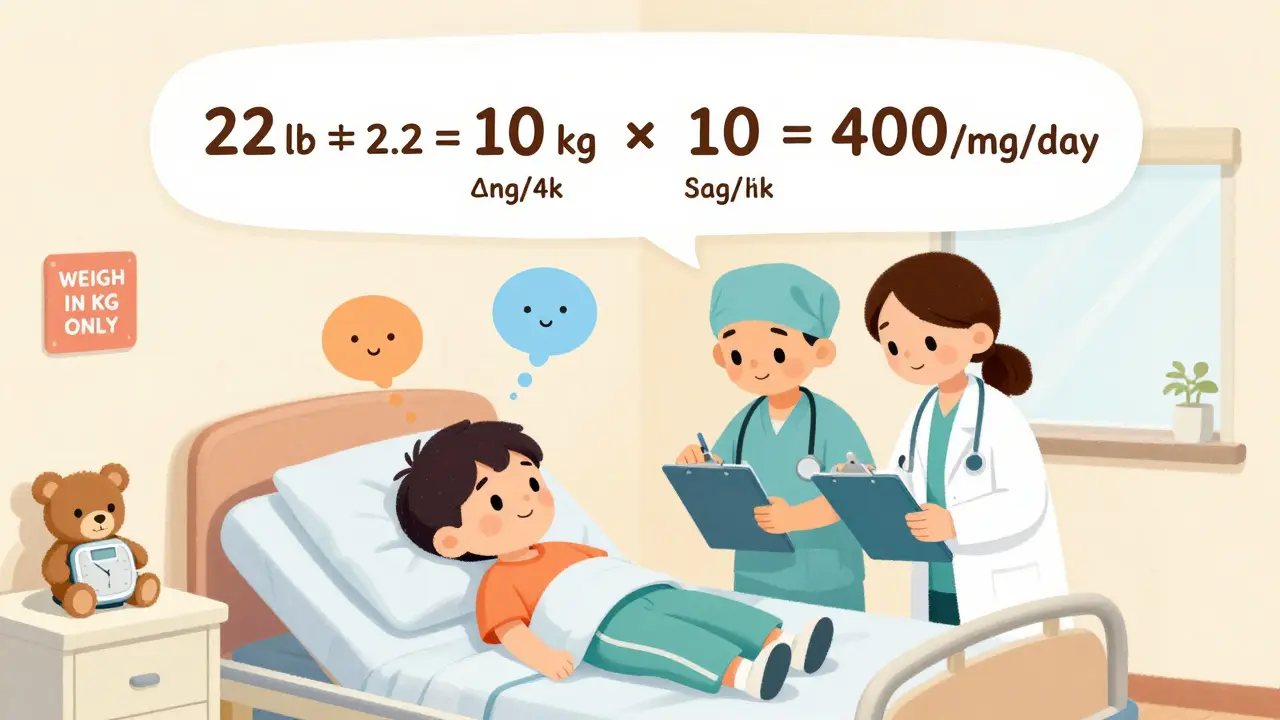

For decades, doctors guessed pediatric doses based on age: "Give half the adult dose for a 5-year-old." But that’s risky. A 5-year-old who’s small for their age gets too much. One who’s bigger gets too little. Research shows age-based dosing leads to errors in nearly 3 out of 10 cases, especially in kids at the extremes of growth. A 2022 study in Pediatrics found switching to weight-based dosing cuts medication errors by 43%. That’s not a small improvement. That’s a safety revolution. Weight-based dosing means calculating the dose based on kilograms (kg), not years. Most pediatric medications are prescribed in mg per kg per day. For example, amoxicillin for ear infections is often 40-50 mg/kg/day, split into two or three doses. A 10 kg child gets 400-500 mg total per day. That’s 200-250 mg per dose if given twice. Simple? Yes. But only if the weight is right.The Three-Step Calculation

Getting the dose right takes three steps-and skipping any one can cost a child their health.- Convert pounds to kilograms: Use the exact conversion: 1 kg = 2.2 lb. Never round until the final step. A child weighing 22 pounds is exactly 10 kg (22 ÷ 2.2). Round too early, and you throw off everything after.

- Calculate total daily dose: Multiply weight in kg by the prescribed mg/kg/day. If the order is 40 mg/kg/day for a 10 kg child, that’s 400 mg total per day.

- Divide by frequency: If given twice daily, divide 400 mg by 2 = 200 mg per dose.

When Weight Isn’t Enough: Body Surface Area and Adjusted Weight

Most kids do fine with weight-based dosing. But some drugs need more precision. Chemotherapy, for example, uses Body Surface Area (BSA), calculated with the Mosteller formula: √(weight in kg × height in cm ÷ 3600). BSA dosing is 18% more accurate for cancer drugs, but it takes longer-nearly 47 extra seconds per dose. That’s why it’s reserved for high-risk meds. Obese children add another layer. A child with BMI over the 95th percentile has more fat and less lean tissue. Giving them a dose based on total weight can lead to overdose, especially with water-soluble drugs like antibiotics. The solution? Adjusted Body Weight (ABW). The formula: Ideal Body Weight + 0.4 × (Actual Weight - Ideal Body Weight). About 78% of children’s hospitals now use ABW for certain drugs. For lipophilic drugs (fat-soluble), like some anticonvulsants, actual weight may still be used.

The Double-Check: Your Last Line of Defense

Even the best calculations can go wrong. A nurse misreads the scale. A resident types 200 mg instead of 20 mg. A decimal slips. That’s why double-checking isn’t optional-it’s mandatory for high-alert medications. The Joint Commission requires independent double verification for drugs like insulin, heparin, opioids, and chemotherapy. Two licensed providers must independently calculate and verify the dose. One does the math. The other checks it. No shortcuts. No "I’m sure it’s right." One nurse on AllNurses shared how her team caught a 10-fold overdose: a resident ordered 200 mg of amoxicillin for a 10 kg child. The correct dose was 20 mg. The nurse knew the max safe dose was 40 mg/kg/day-so 400 mg total. 200 mg per dose? That’s double the daily limit. The system flagged it. The child was safe.Common Errors and How to Stop Them

The most frequent mistakes aren’t about math. They’re about process.- Unit confusion (38%): Using pounds instead of kilograms. Fix: Always weigh in kg. Train staff. Label scales.

- Decimal errors (27%): Writing 10.0 mg instead of 100 mg-or worse, 100.0 mg when it should be 10.0 mg. Fix: Use leading zeros (0.5 mg, not .5 mg). Never use trailing zeros (10.0 mg → 10 mg).

- Ignoring organ function (19%): Giving full weight-based doses to preterm infants or kids with kidney failure. Aminoglycosides, for example, need 40-60% dose reductions in neonates, even if weight is normal. Fix: Always check renal and hepatic function before dosing.

Technology Is Helping-But Not Replacing Humans

Electronic health records now have built-in pediatric dosing tools. Epic Systems’ 2023 update auto-calculates doses, flags doses outside safe ranges, and blocks orders that exceed maximum limits. Hospitals using these systems cut dosing errors by over 50%. But technology can’t replace judgment. A computer won’t know if a child’s weight was recorded after vomiting and dehydration. It won’t know if the child has liver disease. It won’t catch a handwritten order that says "20 mg" but looks like "200 mg." That’s why the human double-check still matters. Tech supports. Humans verify.What’s Changing in 2025?

The FDA now requires all new drug applications to include pediatric dosing algorithms by 2025. The WHO updated its Essential Medicines List for Children in April 2023, adding weight-band dosing for 127 drugs. The NIH’s Pediatric Trials Network has enrolled over 15,000 children to refine dosing for common meds like amoxicillin, acetaminophen, and seizure drugs. Future advances will include pharmacogenomics-testing genes like CYP2D6 and CYP2C19 to predict how a child metabolizes opioids or antidepressants. Early studies show this could reduce adverse events by 37%. But even with all this tech, weight-based dosing remains the foundation.Training and Competency

Pediatric nurses and pharmacists must prove they can calculate doses correctly every year. The Pediatric Nursing Certification Board requires a 90% pass rate on a 25-question test. No exceptions. Hospitals like Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia require three verification steps for high-risk meds: weight check, independent calculation, and cross-reference with institutional limits. The bottom line? Pediatric dosing isn’t just math. It’s a safety culture. It’s double-checking. It’s asking, "Did we weigh them today?" It’s saying, "That dose feels too high-let me recalculate." It’s putting red stickers on scales and refusing to rush in emergencies. Because when it comes to kids, there’s no room for "almost right."Why can't we just use age to dose kids?

Age-based dosing is inaccurate because children vary widely in size and metabolism. A 5-year-old could weigh 15 kg or 30 kg-doubling the drug dose risk. Weight-based dosing accounts for actual body size, reducing errors by 43% compared to age-based estimates, according to a 2022 study in Pediatrics.

What's the most common mistake in pediatric dosing?

The most common error is confusing pounds and kilograms. Using pounds instead of kg leads to 10-fold overdoses. For example, a 22 lb child (10 kg) given a dose calculated for 22 kg gets 2.2 times too much. This accounts for 38% of all pediatric dosing errors, per ISMP 2023 data.

Do obese children need different dosing?

Yes. For water-soluble drugs (like antibiotics), use Adjusted Body Weight (ABW): Ideal Weight + 0.4 × (Actual - Ideal). For fat-soluble drugs (like some antiseizure meds), actual weight may be used. About 78% of children’s hospitals follow this guidance from the Pediatric Endocrine Society.

Is double-checking really necessary?

Yes. Independent double-checks by two licensed providers reduce serious pediatric medication errors by 68%, according to the American College of Clinical Pharmacy. It’s required by The Joint Commission for high-alert drugs like opioids, insulin, and chemotherapy.

What about newborns and preterm infants?

Weight alone isn’t enough. Newborns, especially preterm infants, have immature kidneys and livers. For drugs like aminoglycosides, doses often need to be reduced by 40-60% regardless of weight. Always check organ maturity and adjust for developmental pharmacology.

How do hospitals prevent dosing errors?

Hospitals use multiple layers: weighing in kg only, electronic dose-range alerts, mandatory double-checks for high-alert drugs, annual competency testing, and red stickers on scales. Hospitals using EHR dose-alert systems cut errors by over 50%, according to UCSF’s 2023 quality study.

Will technology replace human calculation?

No. While EHR systems auto-calculate and flag errors, they can’t account for dehydration, recent weight loss, or organ dysfunction. Human judgment is still needed to verify context. Tech supports-but doesn’t replace-the double-check.

Man, I remember when my cousin got the wrong dose of amoxicillin because the nurse used pounds instead of kg... she was in the ER for 3 days. 😅

While the weight-based dosing paradigm is undeniably superior to age-based estimation, one must acknowledge the epistemological limitations inherent in relying solely on anthropometric data without integrating pharmacogenomic profiling. The current standard, though statistically robust, remains a crude heuristic in the face of interindividual metabolic variance.

They put red stickers on scales now? That’s cute. Like putting a ‘Do Not Touch’ sign on a toddler’s face. Meanwhile, someone’s still typing 200 mg instead of 20 because they’re rushing between 5 rooms and 3 crying kids. 🤦♂️

Weight in kg only. Double-check. No exceptions. That’s the whole playbook. No magic, no tech, just discipline.

Let’s be real-this whole system is a band-aid on a gunshot wound. Hospitals are understaffed, nurses are burned out, and EHRs crash when you blink. They want us to do triple checks? Good luck when the computer’s down, the scale’s broken, and the kid’s mom just screamed that she didn’t know the kid weighed 30 pounds because she hasn’t seen a doctor since the pandemic. And don’t get me started on how many times I’ve seen a 10 kg kid listed as 100 kg because someone typed it wrong and no one noticed for 3 days. This isn’t safety-it’s performance art with a clipboard.

In Indonesia, we still use age for most meds at rural clinics. Sometimes we weigh kids on fish scales. But you know what? We’ve never lost a child to dosing error. Maybe because we don’t overthink it. Maybe because we love them more than our protocols. 🌿

Wait… so you’re telling me the government didn’t just make this up to control parents? 🤔 They say ‘weight-based’ but what if the scale is rigged? What if the kg is actually a secret unit the FDA uses to track kids? I’ve seen the documents. The red stickers? They’re tracking chips. 🚨

Why are you all so obsessed with American protocols? In Nigeria we use traditional herbs and prayer. Kids heal faster. This weight math is a Western scam to sell more drugs and keep nurses employed. Let the children be

Okay so I just read this whole thing and I’m crying… like… I’m a nurse and I’ve seen a 10x overdose happen… and I’m so tired… and I’m so scared… and I’m so proud of my team… and I hate that we have to do this… and I love this job… and I hate that we don’t have enough time… and I hate that the EHR freezes… and I love that we caught it… and I hate that we have to double-check… and I love that we do…

Y’all act like this is some groundbreaking revelation. Nah. This is just common sense dressed up in a white coat. We’ve been doing this since the 70s. The real story? Why it took 50 years for hospitals to stop treating kids like tiny adults. And why some still do. 🙄

Double-checks aren’t optional. They’re sacred. If you skip one, you’re not just risking a life-you’re breaking a promise. To the kid. To their parents. To yourself.